Time to bunker down....again

The significant sell off on world equity markets during early May has highlighted the ongoing vulnerability of a global financial system that has inherited unprecedented government debt levels as a result of the “repair” of the previous crisis. Over the first week of May, global equity markets lost an average of 7% of their value.

Specific concerns over the debt levels of the Greek government have been known for some time. Why equity markets chose early May to react so dramatically to the possible implications of the Greek crisis is a mystery of market behavior. Perhaps the violent reaction in the streets of Athens to the terms of the IMF and European Greek rescue package highlighted gravity of the change in spending behavior that will ultimately be required in some form in all heavily indebted nations.

The sell-off may also have been attributable to a prevailing view that the previous rally had pushed share market valuations to at least a “fair value” level. With Chinese economic policy now being tightened, buyers that were willing to step in following previous dips in prices through the recovery were no longer present.

Why markets are concerned about Greece

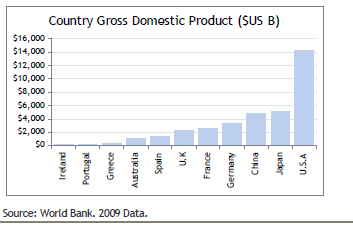

In economic terms, Greece is a small country. As can be seen on the chart below, the size of the Greek economy (and others in Europe with similar debt profiles) is dwarfed by the economic superpowers such as the US, Japan and China. A debt-led economic crisis that saw production slump in Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland would have minimal direct impact on global economic output and the profitability of companies that make up the vast bulk of global equity markets.

Source: World Bank. 2009 Data.

However, as with any crisis in an integrated system, there is potential for contagion effects. Should Greece or other heavily indebted European governments default, or be widely expected to default, then the banks who have lent money to these governments (by buying government bonds for example), would experience losses in the value of their assets. This would then force these banks to scale back other lending in order to preserve capital. Doubts could be created over the solvency of these banks. As was shown during the GFC, once there is a loss of confidence in the

financial system, credit markets can dry up rapidly and the global economy cannot function normally without an ongoing supply of credit.

How valid are these concerns?

The scenario described above may seem eerily similar to the GFC. However, whilst there are never any certainties in economics, the possibility that the Greek debt crisis will trigger a second wave event of the magnitude of the GFC seems remote.

Unlike the sub-prime loan crisis that was seen to trigger the GFC, government debt problems have played out relatively frequently over past decades. For example, the Asian debt crisis of the late 1990s and the Latin American debt crisis of the early 1980s were hugely significant economic upheavals for the countries involved, yet failed to seriously derail the global economy.

It could be argued that because Greece is integrated into the European Union (EU), there is a greater prospect for its debt problems to spread more broadly – via a loss of confidence in the Euro currency for example. However, Greece’s ties to the EU greatly increase the incentive for other EU members to work towards a solution and stem any potential contagion effects.

The size of the EU relative to the size of the problem debt suggests it is likely that the debt problem will be managed with limited contagion. To put this in perspective, the size of Greek government debt is approximately 2.6% of the size of the value of annual production in the EU. Faced with the choice of offering further assistance to Greece or risk a systematic breakdown of the European financial system, authorities in Europe are likely to opt for the former.

It could be worse

With all the focus on debt levels in Europe, there has been a lack of apparent concern over debt levels in the US. In fact the US dollar has gained support in recent days and US government bonds have risen in price. This should be a cause for some relief. Given the size of the US economy and the importance of the US consumer in driving global demand, a US-based crisis in confidence would pose more far reaching risks than the existing concerns over some smaller European economies.

Whilst the most likely scenario is that debt positions in Greece and other European nations will be managed, albeit with some austerity measures that will lower spending and economic growth, clearly equity markets are nervous. This nervousness was hidden in the initial stages of the recovery by obviously cheap valuations. However, now that valuations are closer to a “fair value” level, there will be less buying support in market corrections and investors may have to bunker down for a period of higher than average volatility.