Growing risks for the Australian economy

Key points

-

2008 is likely to see growth remain reasonably strong in Australia due to solid investment and exports.

-

However, the risk of a hard landing for the economy in 2009 is rising if the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) goes too far on interest rates amid the global downturn.

-

The growing interest rate threat may act as a dampener on the relative performance of Australian versus global shares over the next six to 12 months.

Introduction

For many years, the Australian economy has not been a problem for investors. The last recession was 18 years ago and, in recent years, growth has been solid, inflation has been under control and interest rates have been rising (though at relatively benign levels). These factors have underpinned strong profit growth. While the outlook remains reasonable, the risk of a hard landing in 2009 is rising on account of the combined effects of an increasingly hawkish RBA and a downturn in the global economy.

Reasons for optimism, at least for the short term

While the US, Japan and UK are flirting with recession, Australia should be reasonably resilient, at least for now:

- Investment activity is likely to remain strong due to a long pipeline of mining and infrastructure projects

- Australia’s housing shortage should serve to underpin housing construction, in contrast to the US where there is a massive housing oversupply

- Rural production is likely to be boosted by the (apparent) end of the drought

- Price increases of 60% to 80% for iron ore and coal will add just over $2 billion a month to export earnings

- Australia’s high exposure to strong growth in China and Asia and low exposure to the US provide a buffer.

Consistent with this, the Westpac/Melbourne Institute’s leading indicator continues to foreshadow reasonable growth head, at least in the short term.

The Reserve Bank gets tough

The RBA’s recent tightening (despite rising global uncertainty and additional increases in bank lending rates) and the associated rationale indicate a much tougher stance on inflation. In essence, the RBA is now forecasting inflation to remain above or at the top of its target range to mid-2010. It has clearly stated that growth in demand must slow significantly to contain inflation. As such, the bank has indicated that ‘monetary policy is likely to need to be tighter in the period ahead.’ In the absence of a major collapse in global or domestic growth relatively soon, this is obviously pointing to further rate hikes, with the next move probably coming next month. In fact, money market pricing implies an 85% probability of another tightening in March and another move is largely priced in thereafter.

The RBA is undoubtedly employing an element of jawboning to encourage Australians to slow their spending. However, with interest rates rising, the risk that they go too high and produce a hard landing in 2009 is becoming increasingly significant. With investment activity in the economy likely to remain strong, a lot of the brunt of the slowdown in growth required by the RBA will have to fall on consumers. There are several points to note about this.

First, there are several reasons why interest rates have not yet had the desired impact in slowing growth. These include: the impact of offsetting influences such as tax cuts and the boost to national income from higher commodity prices; strong wealth gains from higher share markets (until recently); and the fact that much of the rise in household debt has been amongst older higher income households who are less affected by higher interest rates. While interest rates have not yet achieved the desired slowdown in growth and inflation, this does not mean that they will just keep rising without impact.

The last two tightening cycles (1994 and 1999/2000) had happy endings, however this has not always been the case. The longer and higher interest rates rise, the greater the risk. The experience of the late 1980s/early 1990s highlighted just how hard it is to know where the “tipping point” for the economy is with respect to interest rates. Between January 1988 and November 1989, the cash rate was increased from 10.6% to 18.2% and mortgage rates rose from 13.5% to 17%. For most of this period, there was little apparent impact as growth remained strong, unemployment continued to fall (reaching a low of 5.6% in November 1989) and inflation rose. Then, in late 1989, the economy suddenly began to falter. By the time the RBA started cutting interest rates in January 1990, the economy was heading for “the recession we had to have”. By the time underlying inflation peaked in June 1990, the economy was already in recession!

Of course there are significant differences between the situation now and that of the late 1980s. Interest rates and inflationary expectations were much higher, changes in interest rates were not clearly communicated and business debt was the major issue back then. But the 1989/90 experience highlighted how hard it is to know where the tipping point is and that, once passed, it may be too late to turn the ship around.

Second, if consumption is to bear the brunt of the slowdown, it comes with greater than normal risks this time around. This is because the household sector is saving less and is far more indebted today. The ratio of household debt to disposable income is now over 160%, compared with 40% in 1989. Debt servicing costs are now eating up around 14% of household disposable income compared with circa 7% in 1989. These factors also underpin very overvalued houses. While much of the rise in household debt has been in older, higher income households, there has still been a significant general increase in debt levels. This includes young families with a mortgage, the group most at risk right now.

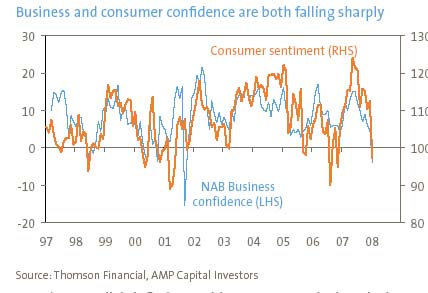

Third, there is increasing evidence that the tipping point may have been, or be close to being, reached. Mortgage stress is at record levels and is still rising, housing finance is showing signs of softening again, weekend auction clearance rates are starting to come in below year-ago levels and consumer and business confidence are now falling sharply, with business confidence at its lowest since 2001.

Fourth, Australia’s inflation problem appears to be largely due to supply side problems rather than strong demand. Key areas behind the rise in inflation over the last two years have been fuel, food, alcohol and tobacco, health and housing (rents). The forces behind inflation in these areas apparently owe more to supply side problems, or global forces, which are little affected by interest rate driven demand management. In fact, in the case of housing costs, higher interest rates may actually exacerbate the problem to the extent that they further dampen housing construction. This could worsen the housing shortage and produce higher rents. It is worth noting that retail price inflation in Australia is running at just 2.5% year-on-year. The problem is, supply side problems are continuing to elevate price gains in key areas. Thus, to bring overall inflation back to target, higher interest rates will have to have a big negative impact on prices in the rest of the consumer price index basket via much weaker consumer spending.

Finally, there is a risk that the RBA is underestimating the impact of the global downturn on Australia. The impact of higher coal and iron ore prices on domestic demand will likely be mitigated if the Federal Government finds greater budgetary savings. More broadly, the recent slump in business and consumer confidence is tracking the decline in US confidence measures, which will help to drag down growth. The local share market has also fallen sharply providing a negative shock to wealth.

Overall, there is a growing risk that the RBA will go past the point on interest rates that will tip the economy over into a hard landing in 2009. It is worth noting that until about six months ago, all major global central banks appeared more concerned with inflation than growth. The US Federal Reserve was the first to switch its focus to growth, followed by the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada and the Bank of Japan. Even the European Central Bank is now relaxing its anti-inflation rhetoric. The RBA is the odd one out, but it too is likely to change its tune by year-end. However, by then, rates may be much higher.

What does this all mean for investors in shares?

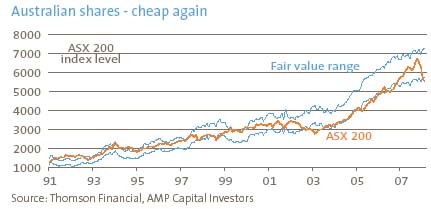

The threat of higher interest rates and a harder landing for the local economy next year, with obvious implications for profits (which are already slowing rapidly), are likely to act as a dampener on Australian shares. Fortunately, the market is now cheap, trading at the low end of our fair value range, which should provide a buffer. But from a broader perspective, after outperforming global shares every year between 2000 and 2007 (excepting 2003), the more aggressive stance on local interest rates will likely constrain the relative performance of Australian shares over the next six to 12 months. This could possibly see them underperform global markets.

Rising local interest rates further complicate stock picking. Consumer stocks and other sectors exposed to the Australian economy were seen as attractive given the uncertainty around globally exposed stocks and financials. This is no longer the case.

Conclusion

In the short term, the Australian economy should see reasonable growth, but the risks are rising with the RBA tightening aggressively amid a deteriorating global outlook. Rising Australian interest rates may act to constrain the relative performance of Australian shares.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors