Household Debt and Wealth

Key points

- Household debt has risen to record levels, particularly in English-speaking countries such as the US and Australia.

- Many are concerned that this means that the next economic downturn will be severe, particularly when combined with an unwinding of leverage.

- The risks should certainly not be ignored, but the problem is not quite as bad as it appears.

Introduction

Over the last sixty years, rising household debt has driven an increase in private sector debt, which now exceeds pre-1930s Depression levels. This has fuelled concern that the next economic downturn will be very severe, as leverage unwinds and consumers are forced to drastically lower spending. In this context, many view US sub-prime mortgage problems as a precursor of things to come, but how real is the risk? Our assessment is that while households are vulnerable, the likelihood of a serious blow-up remains low.

Household debt on the rise

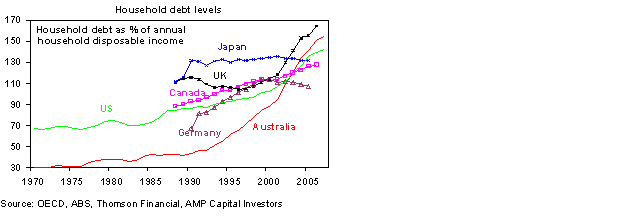

The increase in household debt (mortgage, credit card and personal debt) relative to income has been a global phenomenon for many years.

Australia’s comparative position has shifted from the bottom of the pack to near the top. In 1990, average household debt was equal to six-months average net household income. Today, it is equivalent to 18-months after-tax income. This reflects many factors. Lower interest rates and greater economic stability have eased access to credit and fuelled the demand for “instant gratification”.

Increased debt has led to increased risk

The rise in household debt has increased household vulnerability to factors that threaten asset values and debt-servicing capacity. The main threats are:

- Higher interest rates. Today, moves in Australian interest rates are three times as potent as they were 15 years ago. But central banks, including the Reserve Bank of Australia, are well-aware of the risks and thus, arguably, more cautious. The interest rate threat remains in Australia, but is receding in the US. The US Federal Reserve is moving to lower rates, but this will provide little relief for sub-prime borrowers who face resets to higher rates and difficulty arranging refinance. At present, the main risk stems from lenders passing on higher market rates to consumers, but this is unlikely to cause a major problem.

- Rising unemployment. High debt levels aggravate the risk that rising unemployment will create debt-servicing problems if the economy falls into recession. The risk of this occurring in Australia is low, but has increased in the US.

- A collapse in asset prices. Sustained declines in house prices could undermine the collateral for mortgage debt and cause severe damage. There is now a real risk of this occurring in the US.

- Spontaneous de-leveraging. Another risk is that households, alarmed at their high debt levels, might take spontaneous measures to reduce them. But, unless there is a specific trigger, this seems unlikely.

Sub-prime US mortgagers are in trouble, but there are several reasons why the risk of a generalised household debt implosion is not as great as some fear. The increase in debt is not as significant as it appears, and authorities have extensive scope to respond to problems as they arise.

Rising debt is not as serious as it looks

Increasing household debt is not as bad as it may seem:

- Household debt has been rising since credit was invented. In part, the surge since the 1980s reflects a rational adjustment to greater credit availability, owing to increased competition and lower rates. The definition of what a “safe” level of debt actually is remains unclear.

- The rise in household debt reflects a rational response to reduced economic volatility. Prior to World War Two, economic downturns were more acute and more frequent. However, the economic cycle has become less pronounced over the last 60 years, and improved economic stability has made debt less risky (due to reduced interest rate volatility and enhanced income security).

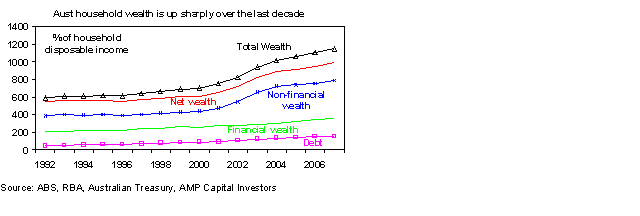

- The rise in debt has been matched by a rise in wealth. In 1992, the average value of household wealth in Australia was six times that of average annual net household income. Today, that value is 11 times greater. The average level of debt for each person in Australia has increased from $14,500 ten years ago to $48,500 now, but the average wealth per person has also increased, from $122,100 to $339,100.

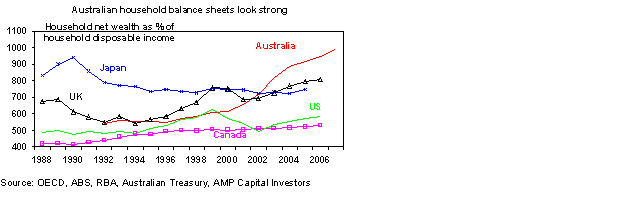

Australian household balance sheets, as measured by net wealth (assets less liabilities), are very healthy.

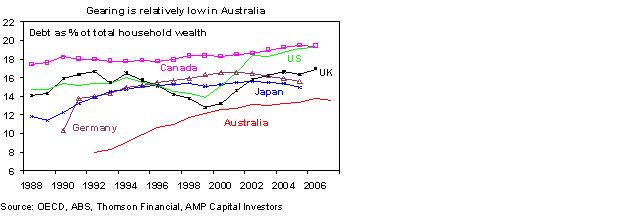

The US situation is less favourable than Australia’s, however increased debt in the US corresponds with a rise in wealth over the last decade (net wealth relative to income has increased). Gearing in Australia has also grown, however it has come from a low base and is below that of other countries.

- Australians appear to be able to easily service their loans. Mortgage delinquencies have increased, but remain low at circa 1%, compared to 5% in the US. Australia’s proportion of non-conventional loans (such as sub-prime and “low-doc” loans) is also nominal, at around 8% compared to 24% in the US.

Debt in Australia is concentrated in high-income households, which have the capacity to service it. The rise in household debt over the last decade has been supported by Australia’s relatively stable business borrowing and public sector budget surpluses.

Debt, interest rates and economic policy

Steadily rising debt levels have characterised the post-war period. Each financial crisis is accompanied by concern that methods of reflation (such as interest rates cuts) will fail, and increased leverage will inevitably produce economic collapse. But instruments of monetary policy have always worked, and there is no reason to believe that the current situation will be any different.

In the US, the authorities are sufficiently empowered to manage the current crisis to ensure that a major downturn does not develop. In addition, interest rates are well-above zero and the US fiscal deficit is significantly lower than earlier estimates. US federal debt (at 38% of GDP) is also well-below the recent average, and there is still potential downside in the US dollar (US$), which will cushion US economic growth. In Australia, there is even more flexibility to respond to household sector problems. Interest rates are higher than normal, the Federal Budget is in surplus and the Australian dollar (A$) is above long-term average levels.

If foreign investors withdrew funds from Australia or the US, this could potentially cause a collapse in local currencies and hinder the authorities’ ability to respond. However, the likelihood of this eventuating is low, as capital supplying countries know that such an event would destroy the markets for their exports. In recent times, these countries have strongly resisted sharp falls in the US$ because of the appreciative effects these falls have on their own currencies.

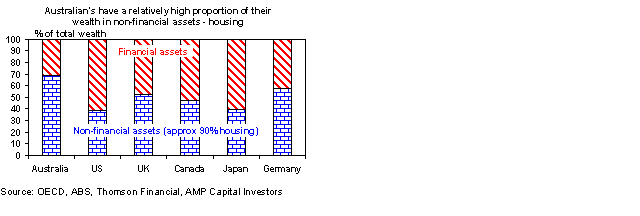

Australia’s high allocation to non-financial assets

International comparison reveals Australia’s unmatched allocation to non-financial assets. 69% of Australian’s wealth is in non-financial assets, compared to an average of 47% across the US, UK, Canada, Japan and Germany. Housing comprises 90% of non-financial assets, reflecting Australia’s love affair with bricks and mortar.

Conclusion

The rise in household debt poses clear risks to the outlook, particularly in the US. However, the risk of a major catastrophe remains low. Growth in debt has been matched by increased wealth, demonstrating a rational response to reduced economic volatility and lower interest rates. In any case, there is considerable scope to reduce interest rates should things go wrong.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors