Strong investment returns – is it just a liquidity boom?

Key points

-

Liquidity conditions are providing a favourable backdrop for investment markets. There is no shortage of funds available for investment opportunities ranging from corporate debt and non-residential property to hedge funds and private equity.

-

With the benign global economic environment likely to continue, this is expected to remain the case.

- So far the run of strong investment returns reflects fundamentals. But if liquidity conditions remain favourable as expected then the liquidity driven boom that many worry about may still be ahead of us.

Introduction

An often expressed view is that the surge in investment returns in recent years reflects a liquidity boom fuelled by easy money. If the liquidity driven view of strong investment returns is correct then sooner or later it must all end in tears. But it’s not so simple. While the liquidity backdrop for investment markets has been favourable, there is little evidence that asset prices have been pushed to exorbitant levels versus fundamentals – at least not yet!

What is liquidity?

“Liquidity” may refer to several different but related things.

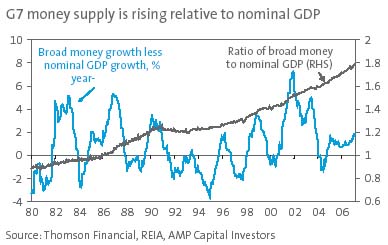

1. The monetary environment – this largely reflects the actions of central banks, with liquidity normally thought to be easy when interest rates are low and money supply measures are growing strongly relative to growth in nominal economic activity.

2. The level of liquidity in balance sheets – are individual or corporate balance sheets cashed up with funds available to invest.

3. The operational liquidity of investment markets – this refers to the ease with which assets can be bought and sold without causing major shifts in current market prices. Markets tend to be most liquid in this sense when confidence is high and funds are flowing freely.

4. The demand for assets relative to their supply – some refer to the analysis of potential sources of demand and supply for a particular asset class as “liquidity analysis”. For example, in the case of shares key demand drivers are individual and superannuation fund flows and cash takeovers, whereas supply is equity issuance less buybacks. Liquidity is high on this measure when potential demand for assets is large relative to their supply. Of course, this concept of liquidity is largely driven by monetary and balance sheet liquidity, but it is also closely related to investor confidence. As such it is easy to confuse this concept of liquidity with changes in investor risk aversion.

The liquidity cycle and current state of play

Liquidity normally follows a cycle that is related to the economic cycle. It is easiest when economic conditions are tough – interest rates are low and balance sheets are cashed up. It tightens after an extended period of economic growth as interest rates rise in response to inflation and companies and individuals allocate their cash to less liquid investments, leaving less to invest in the future. While the economic recovery cycles in Australia and globally are now fairly mature and interest rates have increased relative to four years ago, liquidity conditions still appear to be favourable with no signs of constraints.

- Interest rates in most countries are below nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth. This is particularly so in Japan.

- While broad measures of money supply growth in the US have been relatively subdued, they have been running above nominal GDP growth in the G7 economies as a whole and in Australia. Money supply has been rising versus nominal GDP in most countries.

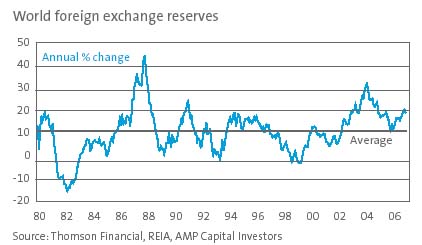

- Foreign exchange reserves are rising rapidly as various countries (notably in Asia and the oil producing nations) seek to prevent their trade surpluses translating into surging exchange rates. The result has been strong growth in domestic liquidity conditions as money is “printed” to buy the foreign exchange and capital is recycled back into global capital markets.

- Strong profit gains on the back of productivity increases have left corporate balance sheets in good shape with low levels of debt and high levels of cash. This is fuelling capital returns to share holders, E.g. via share buybacks and takeover activity, the proceeds from which are normally reinvested. It has also made lowly geared companies the targets of private equity firms.

The result of all this has been ongoing relatively favourable liquidity conditions for investment markets.

This begs the question – is monetary policy too lax?

Has “asset price inflation” simply replaced “consumer price inflation”? This is a common concern, but the answer is no.

- Firstly, consumer price and asset price inflation are totally different concepts. The first is driven by the demand for and supply of goods and services in the economy whereas the second relates to the demand for and supply of investment assets. There are numerous examples in history where asset prices have gone up but consumer prices have gone down, and vice versa.

- Secondly, central banks have been doing the right thing by allowing money supply to rise faster than nominal GDP. Over the past two decades the world has been subject to a positive productivity shock driven by the combination of globalisation (reflecting the increased involvement of China and other emerging countries in the global economy), competition and new technology. These have pushed production up and inflation down. If money supply had not been allowed to grow faster than nominal GDP we would have fallen into deflation and/or the pick-up in productivity would have been stifled.

- Thirdly, central banks alone cannot be blamed for relaxed liquidity conditions. Without an increase in the demand for money and credit it is not possible for a central bank to increase an economy’s broad measures of money supply and credit. Rather, much of the increase in liquidity is a result of strong confidence.

- Finally, as noted below, the surge in asset prices to date has been in line with underlying fundamentals.

So what is happening?

Essentially the benign economic environment of solid global growth and low inflation is the key driving force behind the favourable liquidity environment (and the key thing to watch going forward). This is enabling three key things to happen. First, central banks have been able to run easy or relatively unrestrictive monetary policies. Secondly, it has contributed to favourable balance sheets. Finally, it has fed the confidence of lenders to lend and borrowers to borrow. All of which creates the conditions for both the demand for and supply of credit/liquidity to expand.

Liquidity and investment markets

While liquidity has been favourable, strong investment returns in recent years largely reflect strong fundamentals.

- The shift to low inflation has driven lower interest rates which has in turn allowed yields to fall (or price to earnings ratios to rise) for most assets. This occurred first with bonds in the 1990s, but has only started to happen in the case of non-residential property over the last few years. This can have an exponential effect on asset prices. For example, the shift from a non-residential property rental yield (or cap rate) of 7% to 5% implies a capital appreciation of 40%.

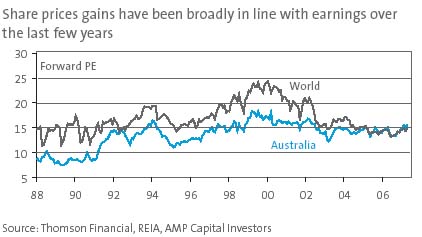

- Secondly, share prices have moved up with earnings. As a result the ratio of share prices to year ahead earnings expectations for global and Australian shares are little changed over the last four years. There has not yet been a liquidity driven blow-off in price to earnings ratio multiples, although this may now be getting underway in Australia.

- Thirdly, the favourable economic environment has led to a low level of corporate debt and defaults – and so corporate debt spreads should have narrowed.

Liquidity likely to remain favourable

While the returns from most investments over the last few years have been in line with fundamentals, this is unlikely to remain the case if as expected the liquidity backdrop remains favourable. As long as inflation remains relatively low, interest rates are likely to remain relatively low and the benign economic environment should ensure that lender and investor confidence remains strong. As a result liquidity conditions should remain solid.

The favourable liquidity backdrop is particularly noticeable in Australia. A combination of takeovers, strong superannuation fund inflows and the start up of the Future Fund have the potential to add at least an extra A$60billion to demand for local shares over the next six months at a time when net capital raising is relatively modest.

Globally, Chinese/Asian and oil-producing countries’ trade surpluses will continue to generate excess capital that will be recycled back into global capital markets. Strong central bank demand for relatively low risk assets like US treasury bonds is displacing private sector investors into corporate debt. This is in turn pushing investors to consider investing in equities which in turn has other investors moving to private equity funds. With the cost of capital remaining relatively low there remains significant potential for private equity takeovers of lowly geared listed companies. Similarly, the yields on non-residential real estate have the potential to be pushed even lower in this context. The end result is that we may be heading into a liquidity driven period in investment markets which has the potential to push price to earnings multiples substantially higher and yields substantially lower.

Dr Shane Oliver

AMP Capital Investors