What will rising interest rates mean for investors?

Interest rate hikes on the way

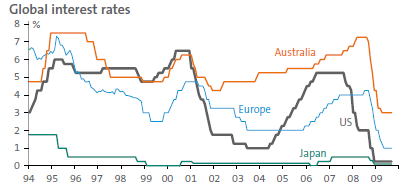

Last year and into early this year, interest rates around the world were cut to emergency low levels to combat the fallout from the global financial crisis.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital Investors

Monetary easing along with fiscal stimulus has been successful. With the crisis fading into history and economic conditions on the mend it’s only a matter of time before interest rates start to move up towards more ‘normal’ levels. This will naturally cause some consternation. However, there are several points to note.

Firstly, the fact that the interest rate cycle is likely to start turning up should be seen as a good thing. Interest rates only collapsed because of the global financial panic and economic collapse. Rising interest rates will signal a return towards normality, i.e. better economic conditions and improving job prospects. Leaving interest rates indefinitely at emergency lows would only encourage too much debt to be taken on and the formation of new asset bubbles.

Secondly, countries that have had relatively mild downturns and/or are likely to return to more normal conditions more quickly are likely to move well in advance of countries that have had deeper downturns and have more fragile financial systems and recoveries. Australia’s downturn has been far milder than expected and a bit of a non event by global standards. The failure of the expected recession to materialise along with improving trends in most economic indicators including housing, consumer confidence, business confidence, business investment, unemployment and forward looking labour market indicators suggest the recovery is becoming self-sustaining and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) will soon start to gradually raise interest rates. We now expect the RBA to begin raising rates before year end and expect the cash rate to reach 5% by the end of 2010.

Similarly, while Asian and emerging countries generally had a sharp downturn in growth, they are recovering very quickly and, led by China and India, are also likely to start raising interest rates in the next six months.

In contrast, the US, Europe and Japan have had very deep downturns, greater increases in unemployment and will likely take longer to recover given various structural problems, including the constrained flow of credit and the desire by households to reduce debt. These issues, along with the likely absence of inflationary pressure for years to come and the need to unwind quantitative monetary easing first, mean these countries are likely to be slower to start raising rates. The US Federal Reserve is unlikely to start moving until around mid next year.

Thirdly, just because interest rates are starting to rise doesn’t mean they are going straight back to previous highs. With inflation being relatively benign, uncertainty regarding global growth remaining and still high household debt levels making households very sensitive to higher interest rates, the process of raising rates is likely to be gradual. In Australia, the RBA is likely to move in occasional spurts and then pause to assess the impact, much as we saw through the 2002 to 2008 tightening cycle.

The initial move higher in interest rates will simply be aimed at returning interest rates to more normal levels now the emergency has passed. But what is ‘normal’? In Australia’s case it has been suggested the normal level for the cash rate is around 5.5% to 6%, which is around Australia’s nominal long-term potential growth rate. However, the gap between bank lending rates and the official cash rate is now around 1% higher than was the case before the credit crisis began. Given this, it’s likely the normal level for the cash rate may have fallen to around 5%. Our view is that the 5% level for the cash rate in Australia won’t be reached until the end of 2010 and that monetary policy won’t move into tight territory (judged to be 6% or more) until 2011 or 2012.

Another way to assess whether monetary policy is tight is when the yield curve becomes inverse (where the cash rate rises above ten-year bond yields) as it is usually only then that economic growth starts to become vulnerable. With Australian ten-year bond yields now at 5.4%, the cash rate has a long way to increase before monetary policy can be described as tight. Similarly in the US, the federal funds rate is now near zero and the ten-year bond yield is 3.5%.

Interest rates and shares

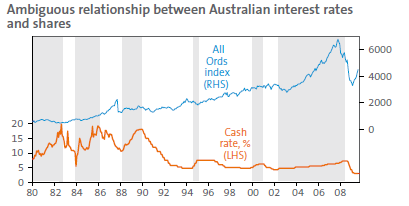

The relationship between rising interest rates and the share market is ambiguous. While higher interest rates place pressure on share market valuations by making shares look less attractive, early in the economic recovery cycle the impact is offset by improving earnings growth. The chart below shows the official cash rate and share prices in Australia since 1980, with cash rate tightening cycles shaded. Sometimes rising interest rates seem to have been bad for shares, as in 1994 for example, but at others times this has not been the case, for example between 2003 and 2007 shares went up as interest rates rose.

Shading indicates cash rate tightening cycles. Source: Thomson Financial, AMP Capital Investors

Several considerations are worth noting. Firstly, rising interest rates from a low base are not normally initially bad for shares as they go hand in hand with improving economic conditions. Just like falling interest rates in a recession are not initially good for shares, as occurred last year. This was evident during the initial stages of monetary tightening in the late 1970s/early 1980s, the 1984 tightening, through 1988 and through much of the 2002 to 2008 tightening.

Secondly, rising interest rates are only a major problem for shares when rates reach onerous levels and contribute to an economic downturn, e.g. in 1981 to early 1982, late 1989 and in late 2007 to early 2008. They are also a problem when rate hikes are aggressive as in 1994 when the cash rate was increased from 4.75% to 7.5% in just four months.

This is consistent with a typical investment cycle which sees rising interest rates only start to become a problem for shares when they reach high levels, i.e. well above normal levels and above long-term bond yields, and inflation is rising.

.bmp)

Finally, given the high short-term correlation between Australian shares (and indeed most share markets) and US shares, what the US Federal Reserve does is arguably far more important than local interest rates.

So in terms of the current situation, while the initial move to raise interest rates may create some jitters, it’s unlikely to be enough to derail the cyclical bull market in shares for the following reasons:

• rising interest rates will reflect economic recovery rather than being a sign of an eventual growth downturn so the improving profit outlook will provide an offset;

• even when interest rates start to rise they will still be very low and with inflationary pressures so subdued it will be some time before interest rates reach onerous levels; and

• US monetary tightening is still nine months or so away.

The key risk will be if central banks move too early and too aggressively to reverse monetary stimulus as occurred with economic policy during the 1930s in the US and in Japan in the 1990s. This is certainly a risk, but policy makers seem more than aware of the risks of a 1930’s-style premature tightening, as evident in the commitment by policy makers at last weekend’s G20 Finance Ministers meeting to maintain stimulus.

Interest rates and the Australian dollar

The Australian dollar (A$) is already up sharply from its US$0.60 low last year. With the already wide interest rate differential between Australia and the US set to widen further and commodity prices expected to rise, the upwards pressure on the A$ is likely to intensify. Another chance at parity against the US dollar (US$) is likely in the next 12 to 18 months. Against this backdrop there is a strong case for investors to maintain a high exposure to fully hedged international equities, as opposed to unhedged international equities which will be adversely affected if, as we expect, the A$ continues to rise.

Concluding comments

The commencement of an interest rate tightening cycle in Australia and later on in other countries may cause some jitters in share markets. However, initial moves will be gradual and interest rates will still be very low for some time. With inflationary pressures very benign, it will probably take several years for interest rates to reach levels that are restrictive enough to hurt the economic outlook and hence shares.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors