Lehman Brothers’ demise one year on

Key points

- The global economy is now in better shape than was the case in the aftermath of the Lehman Brothers’ collapse a year ago. Money and credit markets have improved dramatically, share and commodity markets have rebounded and economic indicators are recovering.

- The key lessons from the sub-prime mortgage crisis and associated debacle are that there is still a business cycle, monetary and fiscal stimulus still works and, in view of the manic nature of human behaviour, sound regulation of the financial system is essential.

- For investors, the key lessons are: that higher returns come with higher risk; be wary of financial engineering and products that are too hard to understand; be wary of having too much debt; and don’t think that having a well diversified portfolio of growth assets will necessarily protect you in a financial panic.

Introduction

It has been 12 months since US investment bank Lehman Brothers failed and set off a roller coaster ride for the global economy. Money markets and credit markets seized up; shares crashed taking US shares to their worst bear market since the 1930s and Australian shares to their worst slump since 1973-74; global trade went into free fall as a result of a slump in confidence and trade finance; and the world economy was knocked into its first contraction since the 1930s. Talk of a re-run of the Great Depression became increasingly common. Fortunately, the world has pulled back from the brink and is now in far better shape. But is the recovery for real and what have we learned from the global financial crisis (GFC)?

From debacle to deliverance

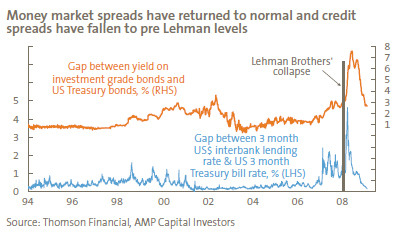

Signs of improvement are virtually everywhere. Firstly, money markets are almost back to normal and credit markets have improved dramatically. As indicated in the next chart, the gap between three month US$ interbank lending rates and US three month Treasury Bill rates, which blew out to almost five percentage points in the aftermath of Lehmans’ demise as banks stopped lending to each other, is now back within the range that prevailed before the sub-prime mortgage crisis started in 2007. Similarly, the gap between US investment grade bond yields and US Treasury bond yields has fallen from over seven percentage points to below three percentage points. Similarly, the flow of lending via credit markets has started to improve.

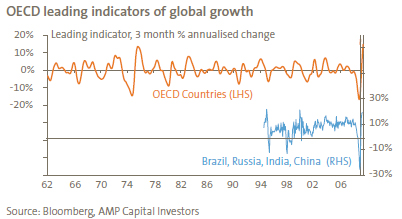

Secondly, economic indicators in most countries seem to be rebounding almost as quickly as they collapsed. This is illustrated in the OECD’s leading economic indicators, which are combinations of indicators such as consumer confidence and building approvals, which lead future activity. After going into free fall late last year they have now rebounded very strongly both for rich countries and for developing countries such as Brazil, Russia, India and China. Many countries have already recorded a strong rebound in growth in the June quarter, particularly in Asia.

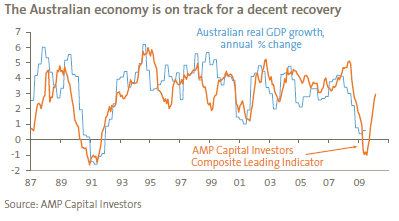

It’s a similar story in Australia. Late last year AMP Capital Investors’ Leading Composite Indicator of Australian economic growth was in free fall reflecting collapsing consumer and business confidence and falling building approvals. The collapse in the global economy looked like it was going to tip the Australian economy into severe recession. In the event, the downturn has been mild and the leading indicator is now pointing strongly upwards, suggesting a recovery is on the way.

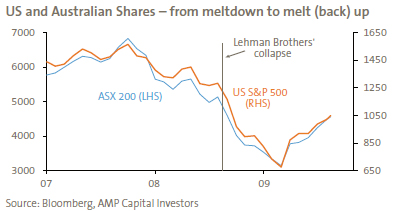

Finally, share markets have rebounded. After Lehman Brothers’ demise, share markets worldwide literally melted in value as investors came to price in the possibility of something like a depression. As the risk of this has faded, and with economic recovery in fact looking like a better bet, share markets have simply headed back up.

Similarly, industrial commodity prices and growth oriented currencies like the A$ have also rebounded back to around the levels prevailing before Lehman’s demise.

So why the upswing?

Just as many analysts were surprised by the speed with which doom and gloom took over late last year, the upswing has been equally dramatic with the prognosticators of doom wondering what they missed (or just declaring that the day of reckoning has just been postponed.) So, to what do we owe this deliverance from the global financial crisis? Australia’s relative resilience owes to a range of factors specific to Australia, such as a stronger and better regulated financial system, a housing shortage as opposed to a housing over supply and continued strong demand from China for our raw material exports. Similarly, the rapid rebound of Asian countries owes much to the region’s lack of a debt constraint and continued strong domestic demand, so that when exports stabilised growth could bounce back.

But the one factor that stands out globally is the swift reaction of policy makers. Just as we saw the worst financial crisis since the 1930s, we also saw the biggest global policy stimulus ever on record. Essentially, practical economists and, most importantly, economic policy makers learned the lessons of the 1930s well – there is a role for Government to fill the breach when private demand dries up and that when there is a financial crisis everything should be done to prevent a collapse in the money supply. As a result, measures to shore up the global financial system were swift and relentless and fiscal stimulus was targeted and timely – it was also complementary between countries unlike in the 1930s. And it’s not right to argue that the rebound is just due to public spending. Yes that is playing a big role. But, more importantly, the stimulus and bank rescue has broken the downward spiral of falling confidence, falling spending, falling asset prices, etc. By stabilising confidence, private spending has been able to stabilise and improve.

Sure, there are things to worry about: How strong will the recovery be, particularly with unemployment still rising and household debt still high? How will the monetary and fiscal stimulus be successfully unwound? And how can the imbalances between surplus and deficit countries be gradually reduced? But these are far better problems to deal with than the human suffering that would have resulted if governments had stood by and let the economy spiral into a deeper recession.

So what can we learn from the GFC?

For investors there are numerous lessons: the investment cycle is alive and well; higher returns come with higher risk; the role of sentiment can’t be ignored; be wary of financial engineering and products that are too hard to understand; be wary of having too much debt; and don’t think that having a well diversified portfolio of growth assets will necessarily protect you in a financial panic.

From a broader economic perspective there are several lessons. First, the GFC has provided a reminder that the capitalist system is inherently unstable thanks in large part to human psychology, and that the idea of an efficient market that can never go astray is completely fallacious. There is nothing new in this. Some neoclassical academic economists may have forgotten, but fortunately most mainstream economists including those in policy making roles are well aware that markets are not always rational and much of macro economics is all about the business cycle and how to deal with it.

Second, there is a role for government to stabilise the economic cycle. Most importantly, policy makers have a decent, albeit not perfect, set of tools in their tool kit to do this. The global and Australian economies have responded well to economic and monetary stimulus, despite the concerns of the doomsayers.

Finally, it should be recognised that ‘stuff happens’. While after each economic crisis there is a desire to ‘make sure it never happens again’ history tells us that manias, panics and crashes are part and parcel of the process of ‘creative destruction’ that has led to an exponential increase in material prosperity in capitalist countries. The trick is to ensure that the regulation of financial markets minimises the economic fallout that can occur when free markets go astray but doesn’t stop the dynamism necessary for economic prosperity. Otherwise, we will end up back where we were in the 1970s by which time post Depression regulation had become stifling to productivity.

No one expects the recovery process to be smooth and easy but at least we are now on the road to recovery.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors