Oliver's Insights - Australian house prices on the rise again - is it sustainable?

Key points

- After falling 6% from their peak, average capital city house prices seem to be on the way up again in Australia. The slump in mortgage rates has drowned out the impact of rising unemployment.

- While the housing correction has been headed off, with Australian housing remaining very expensive, it’s hard to see the housing bubble starting up again.

Introduction

It appears that Australian house prices have defied fears of big declines in the wake of sharp falls in US and UK house prices. My expectation was for national capital city average house prices to fall 10% or so this year. After falling 6% or so from their peak around the beginning of 2008 to the March quarter this year, house prices have started to recover. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data showed average gains of 4.2% in the June quarter, confirming the rise already seen in various private sector surveys. The question is - where to from here? Why has the Australian housing market been so resilient? Are we going to see another unsustainable surge in house prices? And how does housing compare to other potential investments?

Why the resilience?

Despite Australian house prices having had a stronger run up than those in the US and UK, they have fared remarkably well by comparison over the last couple of years. US house prices have fallen 32% from their peaks and UK house prices have fallen 19%.

By comparison, Australian house prices have only had a modest dip and appear to be already on the way back up. Several considerations explain the relative resilience of the Australian housing market. These include Australia’s housing shortage and the fact that lending standards in Australia have been far higher than in the US, with the surge in debt focused on older wealthier Australians. Additionally, the use of full recourse loans in Australia has also provided a powerful incentive to keep servicing a mortgage even when the value of the debt exceeds the home value. These considerations, along with the view that Australia was not going to have US style recession, led us to reject the view that house prices would fall 30% to 40% as some were suggesting. Rather, we thought that prices might fall 10% or so, but even this now looks too pessimistic. The big surprise has been that Australia’s economic downturn has turned out to be even more modest than earlier thought. The economy is yet to have a technical recession and the rise in unemployment has been mild. As such, the generational lows in mortgage rates and the increase in first home owner grants have dominated the housing market.

Outlook

While house prices appear to have turned the corner, we find it hard to see a return to boom time conditions. The positives are that affordability is much improved (see the next chart), Australia is still suffering from a housing shortage, and the upswing in most housing related indicators (e.g. auction clearance rates and housing finance) suggest that confidence has returned to home buyers (both owner occupiers and investors at the top end and the bottom end of the market).

Against this, several factors are likely to constrain the upswing in house prices. Firstly, despite the correction over the last 18 months, Australian housing remains expensive.

-

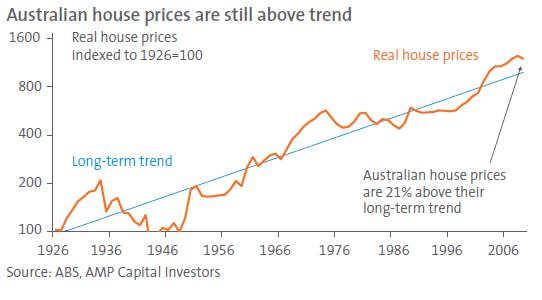

In real terms, Australian house prices remain well above their long-term trend. Over the last 80 years the trend rate of growth in real house prices has been 3% per annum (pa), which is consistent with long-term real GDP growth. However, since the mid 1990s house price gains have been well above trend growth (see the next chart). The historical experience has been that after a run up in house prices to well above trend, they then spend many years working off the excess. This has been occurring in Sydney with average prices generally stagnant for the last five and a half years.

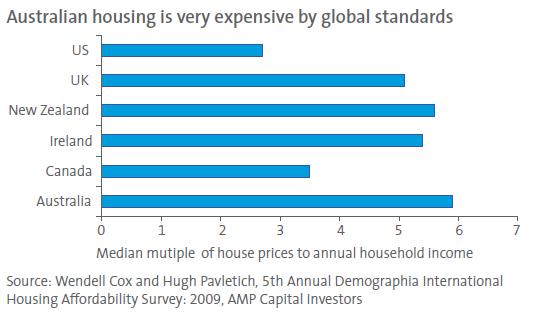

- Australian housing remains expensive by global standards with the ratio of house prices to median household income approximately double that in the US.

- Despite strong growth in rents, rental yields remain low. Gross rental yields of around 5% are well below the 7% plus net rental yields available on directly held commercial property, the 10% distribution yields on listed property trusts and the grossed up dividend yield of 7% from Australian shares.

Secondly, the improvement in affordability has been mainly driven by lower mortgage rates and could therefore vanish fairly quickly if interest rates rise. This contrasts with the US and UK where a surge in affordability has been mainly driven by the collapse in house prices.

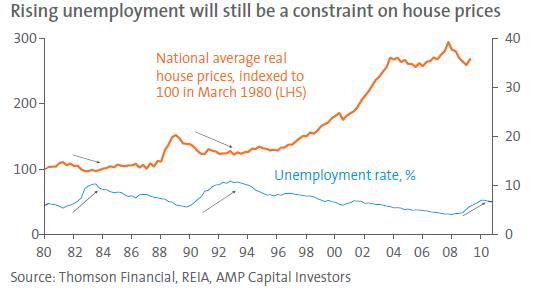

Thirdly, while less of a threat than feared, unemployment is still trending up and poses a constraint on house prices. Historically, rising unemployment has been associated with falls in real house prices. See next chart.

Finally, the ending of the first home owners boost from December will act as a dampener on the lower end of the housing market. These considerations suggest that while a US style collapse has been averted, house prices are unlikely to just go back into boom territory. The more likely scenario is that house prices grow, but at a rate below that of nominal incomes (such that the ratio of house prices to incomes gradually continues to decline).

That said, given Australia’s history with house price bubbles and that much of this can be traced to restrictive land release policies, the risk of another unsustainable surge cannot be ignored. The downside is that having dodged a bullet this time, given Australia’s very high household debt to income ratio, it would leave Australia very vulnerable to the next global economic downturn.

Housing as an investment

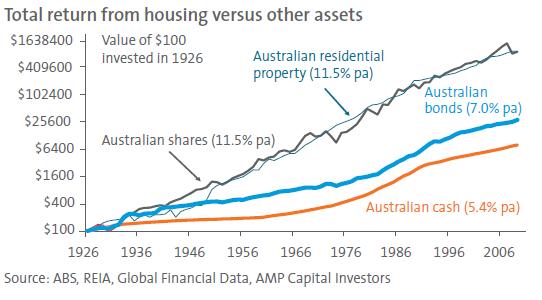

History suggests that once proper allowance is made for costs, residential investment property and shares generate a similar long-term return. This is illustrated in the next chart, which shows an estimate of the long-term return from housing, shares, bonds and cash since 1926.

Over the long term, the returns from housing and shares tend to cycle around each other at similar levels. In fact, both have returned an average of 11.5% pa over the last 80 years or so. While housing is less volatile than shares, it offers a lower level of liquidity and a low level of diversification. The bottom line is that once the similar returns of housing and shares are allowed for, and these characteristics are traded off, there is a case for both in investors’ portfolios over the long term. Right now, after the second worst bear market in the Australia’s share market history and with the yield on shares running well above the yield on housing property, shares are arguably a better short-term bet.

Concluding comments

Due to a housing shortage, less problems with credit quality and a far milder than expected economic downturn, Australian house prices have proven to be fairly resilient. While they now appear to be on the way up again, a return to boom time conditions seems unlikely. Over the very long term residential investment and shares have provided similar returns. Hence, there is a role for both in an investment portfolio.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors

.JPG)

.JPG)