Why relaxing inflation targets would be bad for investors

Key points

-

Rising food and energy prices are leading some to argue that inflation targets need to be relaxed.

-

This would be a big mistake. The 1970s experience tells us that allowing higher inflation to become entrenched will lead to more, not less, economic pain.

-

Sustained high inflation would be bad news for investors as the boost to investment market valuations from the move to low inflation (which drove strong investment returns in the last 25 years) would reverse.

-

A permanent 2% rise in inflation could knock A$140 billion off the value of Australian’s superannuation investments.

Introduction

There is much debate about whether inflation targeting should be abandoned or the target increased. The basic argument is that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) (and other central banks) can’t do much about surging global food and energy prices and that to attempt to do so will result in unacceptable economic pain. In Australia’s case some have suggested the inflation target should be raised from 2% to 3% to say 3% to 4%. While one can debate the appropriate level of interest rates necessary for inflation to meet the current target over time, raising the target itself would be a big mistake. It would entrench the recent rise in inflation and risk taking us back to the slippery slope that led to the high inflation and economic calamity of the 1970s. Moreover, such a move would be disastrous for investors – including all Australian superannuation fund members.

Inflation targeting

Setting inflation targets and charging the central bank with achieving them has been central bank best practice since the early 1990s. It was first introduced as a way of anchoring inflation expectations such that when there is a price shock – such as a sharp rise in food or fuel prices – it doesn’t set off a self-perpetuating wage price spiral like in the 1970s. New Zealand was the first to have a target but now many countries have them. Both the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) target inflation below or close to 2% (although the Fed’s target is not formalised).

Australia’s inflation target was first introduced in 1993 and became formalised in 1996. At 2% to 3% it is actually a little higher than in many other countries. It is also interpreted as being over the course of the business cycle, which means the RBA is prepared to accept inflation being outside the target for a year or two providing it is confident it will come back within the target over the medium term. For example, it currently expects inflation to exceed 3% until 2010.

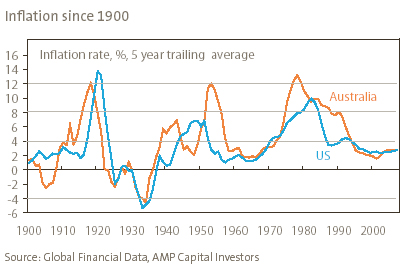

Over the last 15 years or so inflation has been pretty low in most countries. Since 1993 inflation in Australia has averaged 2.6% per annum (pa). This of course is in stark contrast to the 1970s and 1980s when inflation averaged 10.7% pa (with a high of 17.6%) and 8.3% pa respectively. See chart below.

The problem with inflation

After such a long run of low inflation and benign economic conditions it is natural to forget the pain that out of control inflation can cause. In the current environment some see allowing a little bit of extra inflation as a good thing, as a way of avoiding the higher unemployment that might result if we try and bring it to heel. However, this is exactly what was thought in the late 1960s and early to mid 1970s, but the result was disaster. Because inflation leads to higher nominal growth, particularly faster wages growth, it may seem good at first but it is ultimately bad:

-

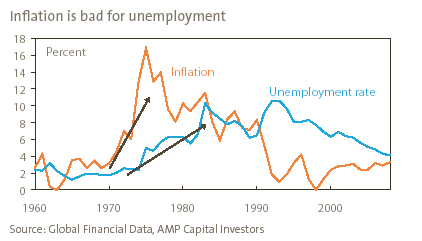

Part and parcel of sustained high inflation is a wage price spiral as workers demand higher wages to catch up to rising living costs. But this just leads to falling international competitiveness, slumping profits and higher unemployment. Whereas it was once thought it was possible to trade off a little extra inflation for lower than otherwise unemployment, the 1970s experience indicated that in the long run there is no such trade-off.

-

High inflation lowers the quality of reported company profits as companies underestimate the cost of replacing assets so they under allow for depreciation.

-

High inflation tends to be associated with a boom bust cycle. In a high inflation world, interest rates have to rise much higher to slow things down so they tend to end up going too far. Extra speculative activity also adds to boom bust tendencies in a high inflation world.

- Finally, the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s highlight that once inflation gets out of control it can be very costly to get it back under control.

So while it may be tempting to go a bit easier on inflation and relax the inflation target, the experience of the 1970s indicates that this would just lead to even worse economic pain. Sure, the move from high to low inflation hasn’t been the only factor behind Australia’s strong economic performance over the last 15 years, but it has been a major driver. It would be a disaster to let the inflation genie back out of the bottle after all the effort that was expended in the 1980s and early 1990s getting it back in.

Sustained high inflation would be bad for investors

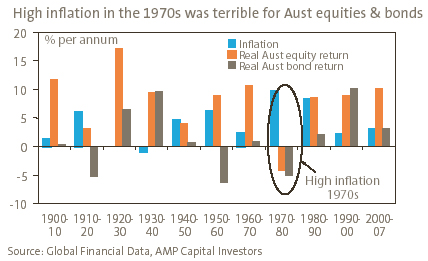

Inflation is of major interest to investors. Beyond short term cyclical fluctuations, the trend in inflation has been the single biggest influence on investment returns since the early 1970s. The combination of rising interest rates (which pushes up bond yields and pushes down equity price to earnings multiples), poor productivity growth, spiralling wages and the poor quality of company profits made the 1970s the worst decade for shares last century (with a real capital loss of 4.2% pa) and the third worst decade for bonds (with a real capital loss of 5.1% pa).

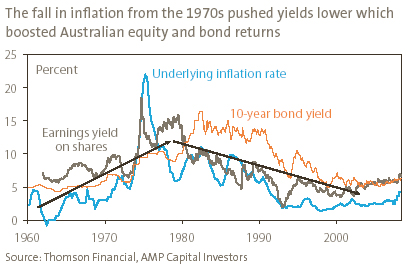

By contrast, the adjustment from high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s to low inflation provided a huge boost to bond and equity returns and more recently to unlisted commercial property returns. The main factor has been the valuation effect of moving from high inflation and high interest rates to low inflation and low interest rates because this has seen the whole yield structure in the economy fall. For equities it was evident in a sharp decline in the earnings yield on shares (or rise in the price to earnings ratio [PE]) since the early 1980s. The earnings yield is of course the inverse of the PE and the latter has gone from a low 5.4 times current earnings in 1974 when inflation was at its highest to around 15 times today. The adjustment from high inflation to low inflation is also evident in the fall in unlisted commercial property yields from 8-9% in the 1980s to nearer 6% today.

Right now assets such as equities, bonds and property are being priced on the basis that inflation will be 2% to 3% over the long term. If inflation moves up by 2 percentage points on a sustained basis it would mean that 10-year bond yields should be averaging about 8%, the PE on the share market should be about 12.5 times and commercial property yields should be about 7%. This would translate to capital losses of roughly 6% on bonds, 16% on shares and 14% on property. If the same happens to global assets it would all knock about 12% or A$140 billion off the value of Australians’ superannuation savings.

Concluding comments

Adjusting inflation targets to allow for the current surge in food and oil prices would risk entrenching high inflation. While it may lead to less short term economic pain it would only lead to worse long term economic conditions. Allowing higher inflation to become entrenched would be very bad news for investors, including super fund members.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors