Australian shares – too cheap to sell

The recent release of December’s labour force figures serve as a timely reminder of just how strong the Australian economy has been. The data showed another 20,000 jobs had been created during the month, allowing the unemployment rate to drop back to 4.3%. Rising employment is unequivocally good news for companies as it provides households with the purchasing power to increase their consumption spending. For banks it also means there are more individuals with the capacity to take on loans and less likelihood of loan defaults.

The substantial correction in Australian share prices we have witnessed in recent weeks belies this ongoing strength in the domestic economy and favourable outlook for the majority of Australian companies. January’s sell-off has largely mirrored global movements where news of big losses being booked by financial institutions has raised expectations of a further tightening of bank credit and a recession in the US.

Is the sell-off justified?

Following the 6% fall in the Australian market in the final 2 months of 2007, the first 3 weeks of January have eroded a further 9% from Australian share prices. Whilst the previous 4 years of share market rallies may have sent share prices to a level that was beyond what could be justified by company earnings growth, the current correction in share prices appears excessive given economic fundamentals.

Certainly a recession in the US would weaken the prospects for the Australian economy and, importantly, would be likely to lower the commodity prices being received by our mining sector. However with our banking sector stable and profitable, household consumption buoyed by ongoing employment growth and our exporters increasingly earning their revenue from the developing Asian region economies, there is a likelihood that the Australian economy will be less impacted by a US led downturn than it has in past economic cycles.

Are shares now cheap?

In times of share market volatility, investors can take some comfort from the continued flow of dividends. As companies tend to pay out only a portion of their profits in dividends, the level of dividends tends to be far more stable than the level of company earnings and indeed the underlying share price.

Given that there is a degree of stability in the level of dividend flow, then comparing the level of dividends to the share price level (ie the dividend yield) is one useful measure that can be used to determine the relative value of shares at a point in time. It is also relevant to compare the dividend yield to the prevailing interest rate at the time, as interest bearing investments represent an alternative to dividend earning shares; whilst the interest rate also represents the cost of funds that many geared investors may be using to fund share market purchases.

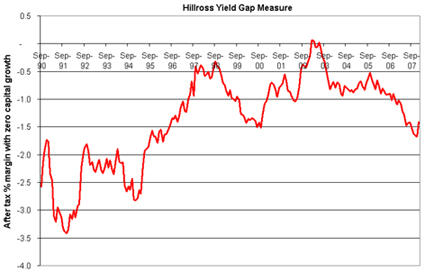

In order provide a guide of share market value that takes into account the dividend yield relative to the prevailing interest rate, Hillross has developed a measure known as the “Yield Gap.” The Hillross Yield Gap calculates the differences between dividend yield and 3-year borrowing cost on an after tax basis. The gap effectively represents what level of capital growth in share prices would need to be achieved in order for a geared investor to breakeven on a share market investment.

The above chart shows the movement in the Yield Gap over time. It can be seen that the gap is typically negative, as interest rates are higher than dividend yields with the difference normally being made up by capital growth in share prices. The exception to this was in March 2003, when dividend yields were above interest costs and this just happened to be the start of the 4 year bull-run in share prices.

Since the beginning of 1990, the average after tax gap between dividend yields and interest rates has been 1.4%. Towards the end of last year the Yield Gap had widened to 1.7% as interest rates were on the rise and share prices moved ahead of dividend yields. January’s correction however, has brought the Gap back towards average at 1.4%, with the dividend yield now around 4%.

Hence, on the Yield Gap measure at least, shares may have been a little expensive towards the end of last year, but now appear to be reasonably valued – albeit still not excessively cheap. Whilst turmoil in overseas markets and economies may well raise discomfort levels for Australian investors for some time to come, caution, rather than panic selling of reasonably valued assets, appears to be what is required.