Avoiding Boiling Frogs

The practice of the Reserve Bank publicly announcing changes it makes to interest rates can still be regarded as a relatively new action. Prior to January 1990, the Reserve Bank would carry out its monetary policy covertly, taking action in money markets to adjust interest rates without making any declaration of its intentions.

The Reserve Bank found however, that the efficacy of monetary policy could be enhanced by an “announcement effect”. By making its actions well known publicly, the economy’s response to an interest rate change was believed to be more immediate and more material. For example, by publicly announcing that interest rates were going to be increased, borrowers were more likely to scale back expenditure earlier and more significantly than if the realisation of higher interest rates came about gradually through other means, such as notifications from lenders.

Loosing impact?

Over recent years the public has become very used to hearing about the Reserve bank changing interest rates. It is possible the impact of the “announcement effect” may fade over time, particularly if the changes in interest rates are of a minor magnitude, such as 0.25%. It could also be argued that when interest rates are exceptionally low, as they are currently, minor changes do little to change attitudes of borrowers who are still motivated to borrow and spend in the knowledge that rates are well below long-term averages.

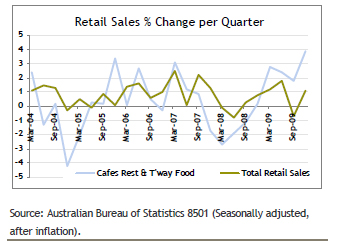

There is some evidence to suggest that the 3 interest rate increases in the December quarter of last year have had minimal impact on the real economy. In recent months consumer confidence has remained steady and retail spending increased by a healthy 1.1% in the December quarter (after adjusting for inflation).

Also of note has been a change in the pattern of retail spending, with the discretionary item of “Cafes, Restaurants and Takeaway Food” the fastest growing (16.4% higher in December than it was a year ago). If high interest rates were having an impact on spending attitudes,

it would normally be expected that discretionary items would be the first to show the signs of moderation.

February’s rate surprise

The fact that there were so few signs of slowing spending in the economy meant that most economists were confident in predicting the Reserve Bank would raise interest again in February. The fact that they didn’t came as a major surprise. However, perhaps the uncertainty over the impact of the previous 3 rate increases has caused the central bank to consider the course of its strategy.

There is a risk that a program of raising interest rates at very small increments is not noticed by consumers or businesses and therefore becomes somewhat ineffective. The impact of increasing interest rates in small increments could be similar to the so called “boiling frog” effect. This boiling frog effect is based around the proposition that a frog placed in water being slowly heated will remain there through to boiling point. No evasive action is taken by the frog because each increment in temperature is too small to be noticed.

0.5% next time?

The decision by the Reserve Bank not to increase interest rates in February may place it in a position to announce a more meaningful and larger increase in interest rates when it next adjusts policy. That is, rather than the Reserve Bank going light on interest rates, February’s decision may have increased the probability of a 0.5% increase in March or April. An adjustment of 0.5% would be an increase worth noticing.