A (slightly) different cycle – ascent of the emerging world

Key points

- No matter how much economic and investment issues change, there will always be a cycle. In other words, history may not repeat but it does rhyme.

- However, the constrained outlook for the US and other developed countries and the relatively strong outlook for emerging countries, along with the emerging world becoming a greater proportion of global gross domestic product (GDP) than the developed world, make this cycle a bit different.

- This has significant implications for investors, pointing to a strategic bias towards emerging markets/Asian shares, commodities and Australian shares.

It also suggests the next big asset bubble may be in emerging markets or related themes – but it has a long way to go yet.

Introduction

One of the most dangerous phrases in the investment world is “this time it’s different”. It usually gets wheeled out near the end of a bull market to explain why the bull market will continue forever due to a new era of permanent prosperity, or near the end of a bear market to explain why the bear market will continue forever due to fundamentally negative forces such as a day of reckoning being upon us. Usually when it is uttered en masse, it marks the turn in the cycle, and makes those who uttered it look foolish. Therefore, the phrase should be used with caution.

However, while the fundamental drivers of the investment cycle – such as human psychology, the tendency for economic growth and asset prices to revert to a long-run mean and the countervailing force of fiscal and monetary policy – remain alive and well, it does need to be recognised that there are subtle differences in each cycle, making them different enough to be of relevance to investors.

There are certainly differences in the current economic and investment cycle that investors should be aware of. This was apparent during the downturn phase, with a financial catastrophe, the likes of which had not been seen in the post-war period, combining with the impact of earlier monetary tightening, an energy crisis and a normal inventory downturn to result in the first slump in global GDP in the post-war period. Moreover, typical cyclical recoveries have seen the US drag the rest of the world out of recession. This time around, it looks a little different.

Uninspiring conditions in developed countries…

While the financial constraints in the US don’t appear to be stopping a recovery, they will likely constrain it after an initial bounce. Following the financial crisis, US credit creation is likely to be impaired for some time and US households are likely to be more focused than usual on reducing their debt levels following the slump in the value of their assets. So notwithstanding the potential for a solid initial bounce as pent-up demand is unleashed, the result is likely to be constrained economic growth in the US for the next few years. This is likely to be reinforced as the US moves towards greater regulation which will increase the cost of doing business in America.

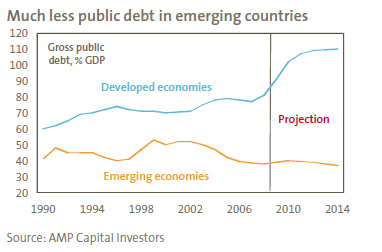

At the same time, structural problems and poor demographics mean it is hard to see either Japan or Europe filling the void. Of course, most advanced countries will also need to deal with very high public debt to GDP ratios which will provide another constraint to growth and a potential source of volatility. Therefore, the overall picture for mainstream developed countries points to sub-par and unexciting growth over the next five years or so. Also, given the substantial amount of excess capacity in the advanced world, combined with subdued credit growth, it’s hard to see inflation becoming a problem any time soon.

Sub-par growth and low inflation mean that monetary policy in developed countries is likely to remain fairly easy. We don’t expect the US and European central banks to start raising interest rates until the second half of next year and tightening in Japan may be two or more years away.

…but inspiring conditions in the emerging world

Emerging countries are not lumbered with the same debt problems as many advanced countries (see the chart above showing public debt), they tend to have far more favourable demographics and they have plenty of scope to boost their own consumption to make up for weaker growth in developed countries and are moving to do just that.

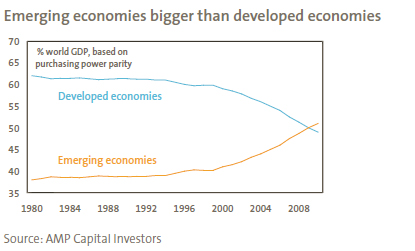

Reflecting this, the emerging world is leading the way out of the global recession with growth in many Asian countries rebounding earlier and much faster than has been the case in the developed world. Not only is the emerging world leading the recovery, but this is the first global economic recovery to occur with the emerging world actually making up a larger proportion of the global economy than the developed world (on a purchasing power parity basis).

While consumer spending is a smaller proportion of GDP in emerging countries, emerging world consumer spending is now equal to that of the US. This sustains the hope that the global economy can be less reliant on US consumers.

Therefore, although there is nothing new in a cyclical economic upswing, the big difference this time around will be the much-greater role played by emerging countries.

What does it all mean for investors?

The greater importance of the emerging world and the constrained, more fragile, outlook for the US and other developed countries have a number of implications for investors. Firstly, investors need to move away from the concept of traditional international equity funds and, instead, allocate more to stronger-growth Asian and other emerging countries. Traditional international equity funds are benchmarked against indices that have an 80% or 90% exposure to slow-growth advanced countries. They are lagging way behind the reality that the emerging world is now playing a much bigger role in the global economy, and that role is set to become even bigger.

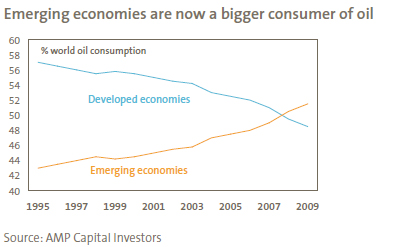

Secondly, growth in the emerging world is commodity intensive as most emerging countries are still rapidly industrialising. For example, emerging countries now consume more oil than developed countries – see the chart below. This suggests an allocation to commodities should also be considered.

Thirdly, strong commodity prices are likely to be favourable for commodity currencies such as the Australian dollar which suggests a need to be aware of unhedged exposures to traditional offshore investment markets.

Fourthly, Australia’s strong exposure to high-growth Asia and commodities, and its rapid population growth provides a positive backdrop for Australian shares and suggests investors should have a bias towards Australian shares.

Fifthly, the greater fragility of US consumers, the risks associated with rising public debt levels (and measures to deal with them) in major advanced countries and the inherent volatility of emerging markets mean that the economic and investment cycle could be more volatile in the future.

Finally, it’s worth observing that bubbles are part and parcel of investment markets and they usually form from the ashes of the previous bust. It’s hard to see another bubble forming any time soon in the US – after all, the US has had a monopoly on major bubbles and busts over the last decade having had both the tech boom and bust and the housing boom and bust. However, the combination of easy monetary conditions in the US and other advanced countries, positive fundamentals in the emerging world and the transition to a more China-centric world mean there is a good chance that the next bubble will be in or around emerging markets and related trades such as commodities. Officials in several Asian countries seem to recognise this and are making noises about the dangers of low US interest rates fuelling a bubble in their own countries. Of course the best way to minimise this is for emerging countries to let capital inflows simply drive up their currencies so that they are then free to tighten their monetary policies to deal with any asset bubbles. However, since the US is unlikely to set its monetary policy on the basis that it may contribute to bubbles in other countries (and why should it) and key emerging countries are unlikely to simply let their exchange rates float higher, the risk of bubbles forming in the emerging world is high. That said, asset bubbles take four or five years to form and it is still very early days yet.

Different enough to matter

Therefore, while there is always a cycle and there will always be bubbles, they are always slightly different. This time around, the rise in the relative fortunes of emerging countries versus developed countries is different enough to have significant implications for investors.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591) (AFSL 232497) makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.