Are we heading into a long-term bear market?

Key points:

- With US financial turmoil intensifying again, shares making new bear market lows and the global economy looking very shaky, it is easy to get very bearish. Predictions of a long-term bear market, based on an unwinding of household debt levels and a slump in consumer spending, are becoming more common.

- While the risks have increased, our assessment is that ongoing action by the US authorities to do whatever is necessary to protect the economy and lower interest rates will head off a long-term bear market in shares.

Introduction

It is easy to get very bearish with financial turmoil in the US intensifying in the wake of the failure of Lehman Brothers and concerns about other companies; claims that the current situation is the worst since the 1930s; shares making new bear market lows; and the global economy continuing to deteriorate. In fact, there are many who argue shares are now in a long-term bear market, led by an unravelling of debt, asset prices, consumer spending and profits. This note reviews the main issues and why we think such a long-term bear market is unlikely.

The long-term bear case

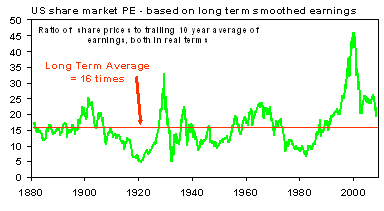

Most predictions of a long-term bear market in shares focus on the US. First, it is argued that shares are not overvalued relative to the current level of company profits, but rather there has been an unsustainable bubble in profits and adjusting for this means shares are expensive. One way of doing this, popularised by Robert Shiller in his book ‘Irrational Exuberance’, is to compare shares to a trailing ten-year average of earnings. This shows the price to earnings ratio (PE) for US shares is still above its very long-term average, and it usually overshoots below its long-term average. The next chart shows this for the US.

Source: Thomson Financial, AMP Capital Investors

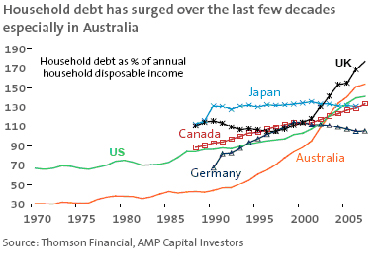

Second, it is claimed by the long-term bears that the bubble in profits has been largely fuelled by a housing bubble in the US and other key countries (including Australia). This has been underpinned by a massive rise in household debt levels and resulted in a consumer spending spree.

Finally, the perma bears argue that thanks to the US sub-prime crisis and resulting credit crunch, the housing bubble is now bursting and this has set off a debt deflation spiral like that experienced in the US in the 1930s and Japan in the 1990s. Specifically, falling house prices result in loss of wealth and reduced consumer spending which means tougher economic conditions, resulting in rising mortgage defaults, less demand for houses and reduced bank lending (in response to mortgage losses), all of which brings about further falls in house prices and so on. It is claimed that the US and UK have already embarked upon this debt deflation spiral – only made worse by the latest bout of financial market turmoil – and that it is just starting in Australia.

Consequently, the long-term bears argue that the bear market in shares has only just begun. This all raises several issues.

What is an appropriate long-term PE?

There are several reasons to believe that the appropriate PE has moved up over time. Share markets today are highly liquid, transaction costs are very low and it is easy to set up a diversified portfolio to reduce risk. Volatility in economic activity and wages has declined dramatically over the last century, resulting in a higher level of investor risk tolerance. These considerations suggest investors would be happy to buy shares on a higher PE today than was the case in the distant past. As a result, the fair value PE today is likely to be higher than it was in 1900 or 1950. If this is the case, it means that even after smoothing out the surge in profits over the last few years, shares are still not expensive.

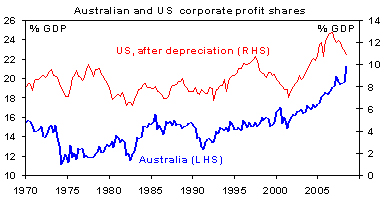

Has there really been a bubble in earnings?

There is no doubt that the level of earnings has increased at an unsustainable pace in recent years on the back of strong productivity growth, more flexible labour markets and the resources boom (in Australia’s case). This has taken margins and profit shares of GDP up to record levels, as is evident in the chart below.

Source: Thomson Financial, AMP Capital Investors

It is to be expected that the profit share will fall back (as is already occurring in the US) and that long-term profit growth will slow to a more sustainable pace. However, there is no reason to expect the profit share of GDP to collapse. The sort of wage pressures that bring about profit collapses did not eventuate through the 2002 to 2007 global economic recovery and look unlikely now that economic activity is slowing.

What is the risk of a debt deflation spiral?

The risk of debt deflation spiral is significant, particularly in the US and UK where house prices are already falling sharply; banks and other financial institutions have sustained big losses (with several in the US going bust); bank lending standards have become very tight (and may become even tighter as banks’ capital bases continue to come under pressure); and the slump in house prices is starting to affect consumer spending. Very poor affordability raises the prospect of something similar in Australia. The intransigence of the European Central Bank, which has been raising interest rates despite the sub-prime related credit crunch, is also adding to the global risks.

However, most economic downturns and bear markets go through a period of heightened uncertainty and concern that the central bank is powerless and effectively just ‘pushing on a string’ because banks don’t want to or can’t lend and no one wants to borrow. This is a common refrain at some point in most economic downturns and bear markets. And this is essentially where we are now. More specifically, while there is much short-term uncertainty and further declines in shares are likely over the next month or so, there are good reasons not to get too bearish.

First, the corporate sector in most countries is in good shape and this provides an offset to weakness in the household sector. This is evident in both the US and Australia in the ongoing strength in business investment.

Second, US authorities have shown they are prepared to do whatever is necessary to prevent a full-blown debt implosion. They moved very quickly to start cutting interest rates and provide fiscal stimulus. In fact, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) started recutting before the US share market peaked in October last year. Furthermore, financial institutions that have run into trouble, such as Bear Stearns, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, have been quickly dealt with, while banks in trouble have been taken over by the federal regulator and their depositors protected. US banks and investment banks have also been dealing with their bad debts quickly.

- This is very different to Japan in the 1990s where the Bank of Japan took 18 months after the share market peak to start cutting interest rates, insolvent banks were allowed to linger on and bad debts were not written off until years later. As a result, deflationary forces were able to take hold, which led to an 80% fall in Japanese shares over 13 years.

- The current situation is also very different to the US in the 1930s where, initially, the focus was on balancing the budget. More than 5000 US banks were allowed to go bust between 1929 and 1933 (taking their customers’ savings with them) and interest rates were actually increased in 1931. This contributed to an 85% fall in US shares over 2 and a half years.

Quick action by US authorities over the last year is reflected in the fact that the US share market has fallen less (down about 22% from last year’s high) than European, Asian and Australian shares (which are down by more than 30%) so far in the current bear market.

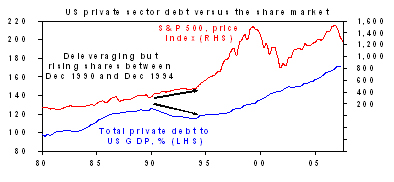

Third, the fall in private debt that occurred in the US in the early 1990s in the aftermath of the savings and loan crisis and commercial property bubble did not prevent economic recovery and a modestly rising share market through most of the period of de-leveraging. See the chart below.

Source: US Federal Reserve, Thomson Financial, AMP Capital Investors

Finally, with consumption a national pastime, it is hard to believe that once interest rates come down sufficiently, Americans and Australians won’t revert to their normal consumption patterns. In this regard, the plunge in the oil price, the ongoing credit crunch and the deteriorating economic outlook will likely see most central banks cut interest rates, including the Fed and the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Concluding comments

For some time we have been of the view that shares would remain weak in September/October, ahead of better conditions later this year and into 2009. While the ongoing turmoil in the US financial system indicates that the risks have increased and that shares may see further downside in the next month or so, our assessment is that a long-term bear market in shares is unlikely.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors