The Chinese Renminbi heading towards appreciation

Key points

- Tensions between the US and China around the value of the Renminbi (RMB) are escalating again.

- The most likely outcome is that China will allow a resumption of modest RMB appreciation of around 7% over the next year.

- On balance, this is likely to be positive for China and Australian mining stocks.

Introduction

Speculation about an imminent move in the value of the RMB has intensified amid rising trade tensions between the US and China. The US Treasury may label China a ‘currency manipulator’ in its looming foreign exchange report (due 15 April 2010) and a group of US politicians are threatening increases in tariffs on Chinese imports. Meanwhile, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao has rejected claims the RMB is severely undervalued and there is a sense that new found confidence may be forcing Chinese leaders to stand up more to US demands.

Nothing new

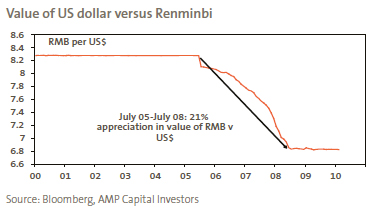

There is nothing new in terms of tensions over the value of the RMB. The US first started to push for RMB revaluation around 2002. By 2005, US politicians launched a bill threatening a 27.5% tariff on Chinese imports. The tensions then dissipated after China revalued the currency by 2% in July 2005 and then allowed it to appreciate. By mid-July 2008, the RMB had appreciated by a cumulative 21% against the US dollar (US$).

With the global financial crisis taking a toll on Chinese exports, China ceased the appreciation in mid-2008, and the RMB has been stuck at around 6.83 to the US$ ever since. With Chinese exports now recovering, RMB appreciation being seen as a way to help deal with inflation and US political pressure intensifying again, expectations for renewed appreciation have returned.

Basic economics – why appreciate?

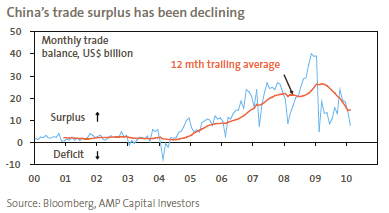

According to the US, the Chinese RMB is severely undervalued and causing immense damage to the US economy. However, this is subject to much debate. First, it is not clear the RMB is actually undervalued. Most measures which compare the purchasing power of currencies show the RMB to be undervalued against the US$. A popular example of this is The Economist Magazine’s Big Mac index which indicates that if the price of Big Macs were to be equated in the US and China, the RMB would need to rise in value by around 50%. However, against this, China’s trade surplus has been declining as its imports have been growing faster than its exports. This is hardly a sign of a significantly undervalued currency.

More sophisticated estimates of fair value from Goldman Sachs, which allow for productivity swings, the terms of trade and relative inflation, indicate the Chinese RMB is actually fair value against the US$.

Second, it is doubtful the RMB appreciation alone will help reduce the US trade deficit with China, as the US is generally not competing in the same areas. Liberalising restrictions on high-tech exports to China would probably do more to redress the imbalance than a currency shift.

Third, China has been a big funder of the US budget deficit via bond purchases, which is only possible as China is buying US dollars to stop the RMB from rising. If this hadn’t occurred, US living standards would be a lot lower.

Given all this, it’s little wonder China is not convinced its currency is dramatically undervalued and that its currency management is causing big damage to the US economy. There are a number of other reasons why China has resisted pressure to adjust its currency or let it float: its capital market is relatively undeveloped; having seen the damage caused by wild exchange rate swings during the Asian crisis it has been reluctant to expose itself to the same; and it is aware of the damage the rise in the value of the Yen (under US pressure) caused Japan in the 1990s. It also sees significant uncertainty around the global recovery and hence in the outlook for its exports.

Against all this, though, there are good reasons for China to resume a modest appreciation in its currency.

First, allowing the RMB to rise will make it easier for China to control inflation as opposed to relying on monetary tightening alone; given it will reduce import prices.

Second, by making imports cheaper, it will help facilitate a rebalancing in the economy towards consumption, effectively better enabling China to take advantage of the slack that currently exists in major advanced countries.

Third, the US$ peg arguably works against China’s national interest. It has effectively meant China’s trade weighted exchange rate has gone up with the US$ during times of crisis, which is exactly the opposite of what’s required. It is also working against Chinese efforts to promote the RMB as a reserve currency. What’s the point if it’s just pegged to the US$?

Likely outcome

China does seem to recognise that a trade war with the US would be far worse than allowing a modest appreciation and there are good economic reasons to adjust the RMB. So, the most likely scenario is that the RMB will resume a path of gradual appreciation against the US$ some time in the next few months. Whether this begins with a one-off revaluation like in July 2005 is hard to tell and doesn’t really matter. Overall, we see the RMB rising by around 7% over the next 12 months. Such a move could also involve a shift away from the RMB being managed against the US$. It would be in the America’s best interests to accept only a modest appreciation; otherwise China could threaten to start selling US Treasuries. This would put upward pressure on US bond yields and hence US borrowing rates and be bad news for the US economy.

Implications of a resumption of modest appreciation

By way of background, the following table shows what happened between July 2005 and July 2008 when the RMB was last allowed to rise against the US$.

What happened when the RMB last rose in value?

|

|

% change June 2005 to July 2008 |

|

RMB versus US$ |

+21% (ie RMB appreciation) |

|

Chinese trade surplus |

+213% (ie rose three fold) |

|

US trade deficit with China |

+39% (ie got worse) |

|

Chinese A shares |

+157% |

|

Asia ex-Japan shares |

+50% |

|

Korean won versus US$ |

+2.2% |

|

Taiwan dollar versus US$ |

+3.2% |

|

Base metal index* |

+101% |

|

Australian resources shares |

+105% |

|

Australian dollar (A$) versus $US |

+24% |

|

Australian exports to China |

+59% |

London Metal Exchange base metal index. Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital Investors

Over that period, the RMB rose by 21% against the US$; China’s trade surplus increased, as did the US deficit with China; regional share markets rose; Asian currencies rose, but only modestly; commodity prices and resources shares rose; the A$ rose by a similar amount as the RMB; and Australian exports to China continued to rise. China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth also remained strong over the period. The appreciating RMB coincided with average GDP growth of 10.9% per annum (pa), which is above the 9.2% pa average over the last decade as a whole. It’s hard to see a big difference going forward.

We see the key implications of the resumption of RMB appreciation being as follows:

- Little impact on China’s overall growth, but with a mild boost to consumption relative to exports. A 7% move is small compared to the huge regular swings in the euro and A$. It’s unlikely to be enough to cause a dent in Chinese exporters’ profitability, who will in any case benefit from reduced raw material import costs. In any case, China is unlikely to let the RMB continue to appreciate if the growth backdrop weakens too much. However, by making imports marginally cheaper, it will help boost consumption.

- Little impact on the US trade deficit for reasons noted earlier.

- Upward pressure on other Asian currencies. The 2005-08 experience suggests this will be mild; maybe around 2-5%.

- Mild positive for commodity prices. Commodities will become modestly cheaper in China and this may boost their demand.

- Positive for Australian exporters, including mining companies, given exports to China will now be cheaper. This will mainly benefit commodity producers.

- Upward pressure on the A$ against the US$. The A$ will likely benefit from higher commodity prices like it did during the last period of RMB appreciation. We continue to see the A$ reaching parity against the US$.

- Marginally higher US bond yields as China and possibly other Asian central banks reduce intervention to stop their currencies rising and hence slow their purchases of US bonds. However, the impact is likely to be marginal as the Chinese authorities will probably have to continue intervention to prevent a rapid appreciation in their currency. Only a move to a free float by China and across Asia would substantially curtail Asian demand for US bonds. However, a move to a free float is probably still several years away.

Concluding comments

Sabre rattling between the US and China could be a source of investment market jitters in the next few weeks, but the most likely outcome will be China allowing the resumption of modest appreciation in the value of the RMB. However, the mild nature of any move suggests the global economic impact will be minor. Australian resources stocks are likely to be beneficiaries.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591) (AFSL 232497) makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.